Why Was Kenya's U-15 Football Team Forced to Sleep Outside?

Whether Olympic athletes or its youth football teams, Kenya has a troubling pattern of leaving its athletes in unsafe travel and sleeping conditions.

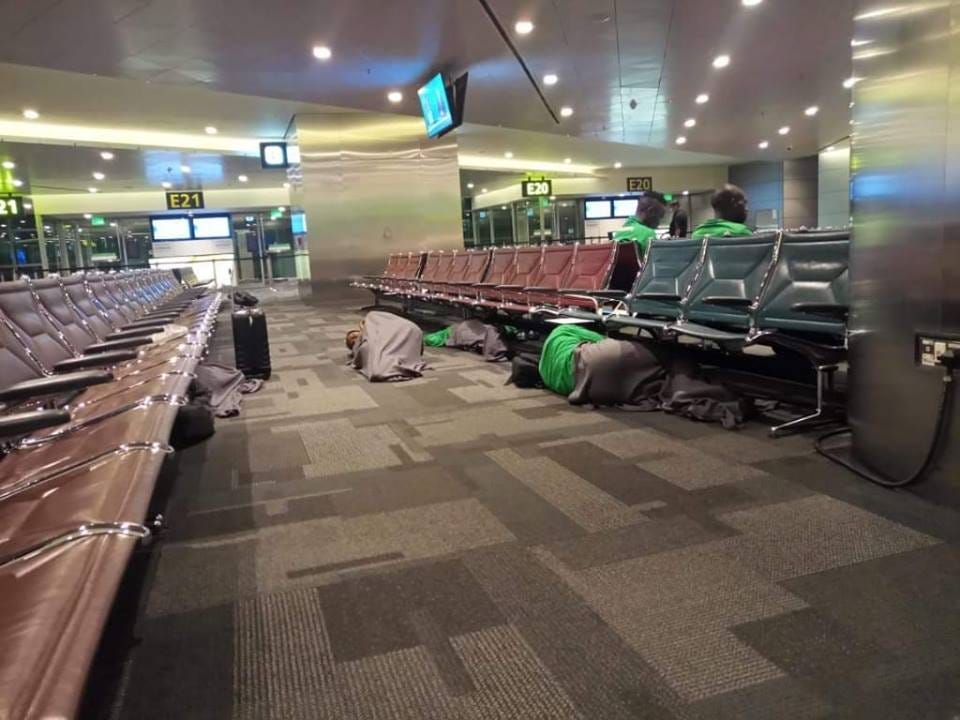

On the night of 10 December 2025, photographs spread rapidly across Kenyan social media showing the country’s U15 boys’ and girls’ football teams sleeping on tiled floors and benches inside St. Mary’s Kitende, a boarding school and host venue in Kampala, Uganda. The teams had just completed competition at the CAF African Schools Football Championship and were preparing to return to Nairobi when their scheduled buses failed to arrive.

The missed departure created a legal quandary. Under Kenyan regulations, junior teams are prohibited from travelling at night. Once the transport delay pushed the departure time past the permitted window, the delegation could not legally travel back to Kenya that evening.

Without pre-arranged alternative accommodation, the children remained at the school overnight, lying on floors, chairs, and benches. The images circulated widely, amplified by prominent Kenyan sports journalists and supporters, and quickly raised questions about planning, safeguarding, and responsibility.

The U15 teams had departed Kenya after compressed preparation timelines, arriving in Uganda just hours before their opening fixtures after a grueling 13-hour road journey from Nairobi. Both delegations performed poorly. The boys endured a heavy 7-0 opening loss to host Uganda and were eliminated in the group stage, finishing third with three points. The girls similarly placed third in their group, collecting just two points from their matches.

How did this happen?

The events of December 10 were no mere logistical accident, but the inevitable result of inadequate contingency planning. Transport delays are operational realities in international youth sports. Under Kenya’s night travel prohibition, the Football Kenya Federation (FKF) knew that delays risked leaving the teams stranded. Yet, they had no backup accommodation arranged.

Kenyan sports sadly have a long history of this.

The Football Kenya Federation issued a statement on December 11, confirming the transport delays and claiming that tournament organisers “CECAFA and St. Mary’s Kitende stepped in to support the teams, ensuring their safety, comfort and access to necessary facilities overnight.”

The federation also said it would “review internal processes” to prevent a recurrence.

Even with that clarification, several practical questions remain central to public scrutiny and require clear answers:

Why was no contingency accommodation booked in advance, given that night-travel restrictions were known and transport delays are common in African regional sport?

Where were accompanying Kenyan officials accommodated that night, and did they remain with the children throughout?

Was CECAFA responsible for providing overnight accommodation, or did this remain FKF’s duty once the competition formally concluded?

Has this happened before?

Kenya’s U15 incident is not isolated. Kenyan sport has a troubling history of athlete neglect spanning the past decade, where poor planning and institutional dysfunction have repeatedly exposed athletes to unsafe or undignified conditions.

Rio 2016 Olympic Games

At the 2016 Rio Olympics, Kenya’s delegation achieved its best-ever Olympic performance with 13 medals: six gold, six silver, and one bronze.

After the Olympic Village closed, a significant portion of the Kenyan delegation remained in Rio for several days longer than expected, not in the village’s comfortable quarters, but in more marginal accommodation. Marathon runner and Team Kenya captain Wesley Korir publicly described being housed near a shantytown, where gunshots were heard overnight and athletes were instructed to stay indoors for safety. Korir documented the accommodation on social media, complaining that gold medallist Eliud Kipchoge had to secure his own ticket home, while others had been left behind.

Members of Kenya’s Olympic organising committee were allegedly sacked by the government with athletes still stranded in Rio days after the end of competition.

The fallout quickly travelled back with the team. Upon arrival at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi, senior officials of the National Olympic Committee of Kenya (NOCK), were arrested for allegedly stealing funds and equipment intended for the Olympic athletes.

Amid the uproar, Kenya’s Sports Ministry under Hassan Wario dissolved NOCK and launched a formal probe into the organisation’s conduct in Rio.

Rabat 2019 African Games

But three years later, the same problem happened again at the African Games in Rabat, Morocco. In August 2019, as Kenya’s national athletics and women’s volleyball teams prepared for competition, they were abruptly evicted from their training camp hotel when the government failed to pay accommodation and meal bills.

The humiliation was compounded by deeper dysfunction: 11 additional athletes and five officials were simply removed at the last minute from Team Kenya’s delegation due to lack of funds, preventing them from competing altogether.

Gor Mahia FC in Morocco - 2019

This pattern has also affected club sides. In April 2019, Kenya’s most successful club side, Gor Mahia FC, flew to Morocco for a CAF Confederation Cup quarter-final against RS Berkane.

But on the day of travel, players and officials discovered at the airport that many of the team had no tickets booked and the club’s travel arrangements were incomplete, forcing them back home and leaving departure uncertain for more than 24 hours. Many had to make frantic efforts to secure alternative flights, including via stopovers in Europe or the Middle-East, instead of flying straight to Morocco.

On April 13, the squad flew from Nairobi to Doha, Qatar, and then to Marrakech, before travelling overland to Berkane. The squad was exhausted and had virtually no time to rest ahead of the match the next day. T

Similarly to the U15 incident, a number of players were reported to have rested on airport floors, while some officials were allegedly accommodated in hotels.

They lost the game in Berkane 5-1.

Is this only a Kenya problem?

While four athlete welfare failures in under a decade is highly concerning, the problem is not uniquely Kenyan.

In July 2025, 25 junior South African soccer players were stranded in Portugal after the BT Football Academy failed to purchase return flights from the Donosti Cup tournament in Spain. The academy cited visa processing delays that led to last-minute flight bookings at prohibitive costs. Many parents had to raise costly sums for their children to get home safely, asking for donations from friends and family.

In November 2024, Nigeria’s national football team was stranded for 16 hours in Libya’s airport during a CAF African Nations Championship qualifier with no food or water provided. The incident was so severe that CAF awarded Nigeria the match points and imposed a 50,000 USD fine on Libya, recognizing it as an extraordinary safeguarding breach.

These are just the latest incidents in a long line of similar crises.

But not much is done. Even after the latest scandal, the FKF has announced no safeguarding audit, investigation, or disciplinary measures specifically addressing the U15 incident. On December 15, 2025, FIFA even lifted a funding freeze on FKF, citing positive governance reforms and improved 2024 audit results. However, this decision was based on financial and governance improvements. Safeguarding was not taken into account.

Excellent investigative work tracing this pattern across multiple incidents. The repeating cycle of inadequate contingency planning, from Rio 2016 to now, shows how institutional failuers compound when there's no real accountability mecahnism. I saw something similar in youth sports logistics in East Africa, where the problem isn't just funding but that organizational knowledge never sticks because leadership keeps rotating. FIFA lifting the funding freeze without considering safeguarding is basically validating dysfunction.